Study finds that explainable AI often isn’t tested on humans

Though artificial intelligence (AI) is becoming more prevalent in our daily lives, many systems are black boxes — data is input, and results are output with only a select few experts understanding how the system fully works. A paper from MIT Lincoln Laboratory shows that though attempts have been made to help humans understand how these systems work, very few systems are actually tested on humans.

In recent years, the use of AI in the public, private, and defense sectors has increased immensely. The technology is used in everything from helping manage smart home devices to giving Amazon recommendations, but it can also be used for safety and defense functions such as administering life-saving medical care, tracking cyber threats, and piloting aircraft. These systems require a certain amount of trust from the user, and one way to gain that trust is for people to understand how these AI systems work.

"The use of AI has skyrocketed in the past few years, especially after ChatGPT’s release," says Ashley Suh, a researcher in the AI Technology and Systems Group. "We’ve become increasingly concerned that AI systems that claim to be interpretable and trustworthy to humans — termed 'explainable AI' — are not actually validated with the humans they’re intended to be understood by."

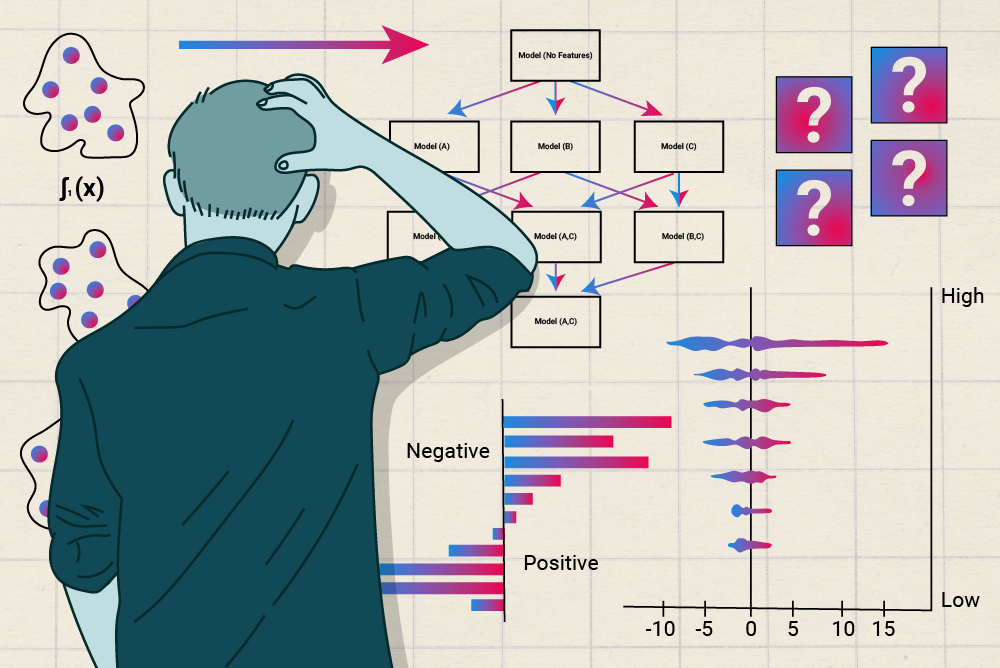

Scientists have developed techniques in explainable AI (XAI) — also called interpretable, trustworthy, or transparent AI — to translate the models' decision-making into a form that humans can understand. XAI methods rely on techniques such as rule-based reasoning, use of examples, and text-based explanations to help humans understand what’s going on. However, it's not clear how many of these systems that claim to be explainable by humans are tested on real people. Suh and a team of Laboratory researchers and archivists set out to understand just how many XAI papers evaluate their methods on humans.

Though there have been previous studies of this kind, they have been limited; two studies examined around 25 papers, while a third study reviewed 300 papers. With the help of Nora Smith, a research librarian, the team reviewed more than 18,000 papers with a focus on the question, “Of all the XAI papers that claim human explainability, how many validate those claims with empirical evidence?”

The team tested their question by parsing the papers. Though they had a clear question in mind, the challenge was to figure out how to find the papers that actually used human testing.

"'Does this paper use human evaluators, yes or no?' should be an easy question to answer, but it gets messy real fast," Smith says. "One challenge for projects like these is crafting a single search that will capture what we want — without too many irrelevant hits — in a reproducible and updatable way. Standard literature searches are a bit like whacking a pinata. You can keep whacking at the problem until you succeed. For documented searches like this, you get one hit, so it needs to be a good one."

The method they settled on was first filtering by XAI papers (using regular keyword searches) and then further filtering those papers based on which ones had claims about humans (which includes subjects such as "human feedback," "end-user evaluation," and "user interview"). This final set was reviewed by the team, who looked through the papers by hand to see whether the papers' explanations of how AI worked were validated with humans through experiments. A paper did not pass the test if it didn't conduct human validation. The only papers that score a "yes" to the question were those that specifically discussed validating their explainability methods with humans.

After going through the papers, they found that half the papers that claim to have human-interpretable AI methods didn’t validate them with humans, and that out of the approximately 1,000 papers that never mention humans at all, less than a dozen of them provide any kind of validation for their claims. Overall, they found that out of the 18,254 papers, only 126 (0.7%) validated their methods with real people.

"We went in thinking the percentage of XAI papers providing human validation would be 40%, or maybe 30% if we were feeling a bit pessimistic. We had no idea it would be 0.7%," Suh says. The issue, the team found, was that the field of XAI provides evidence that practitioners are engaged in AI work, but not that the AI itself is explainable.

"These researchers are relying on loosely defined criteria to signal explainability, such as presenting AI outputs in natural language or ensuring its responses follow some vague measure of conciseness," says Hosea Siu, a researcher in the AI Technology Group. "But these qualities are neither necessary nor sufficient conditions for explainability — the proof is in the evidence that someone has examined an 'AI explanation' and used it in a meaningful way. That kind of validation is what the field is not taking seriously enough. In general, we’re hoping it sheds light on the lack of human validation in a field that claims to support humans in making decisions with AI systems. When you design something that's meant to be interpreted, understood, and trusted by a real person, you ought to test whether it'll work as you intend with that person."

The team presented their results at the Association of Computing Machinery's Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI) in May. One major takeaway from the conference was that lack of validation was not unique to the field of XAI. Researchers from the fields of medicine as well as privacy and security shared that this issue is common in their disciplines as well. The most compelling story they heard was from a researcher in disability studies, who shared that, rather than testing systems with disabled users, developers often "simulate" disability by substituting, for example, a blindfolded sighted person for a blind person when testing tools.

"In some ways, XAI falls shorter, as researchers are rarely demonstrating that their systems support the core claim of human explainability," Suh says. “The stories shared with us at CHI reinforced for us how important it is that we move beyond surface-level evaluations for the sake of saying 'I evaluated my system' and instead holding ourselves and others accountable for involving the people we claim to design for."

Read more on this topic in the team's case study.