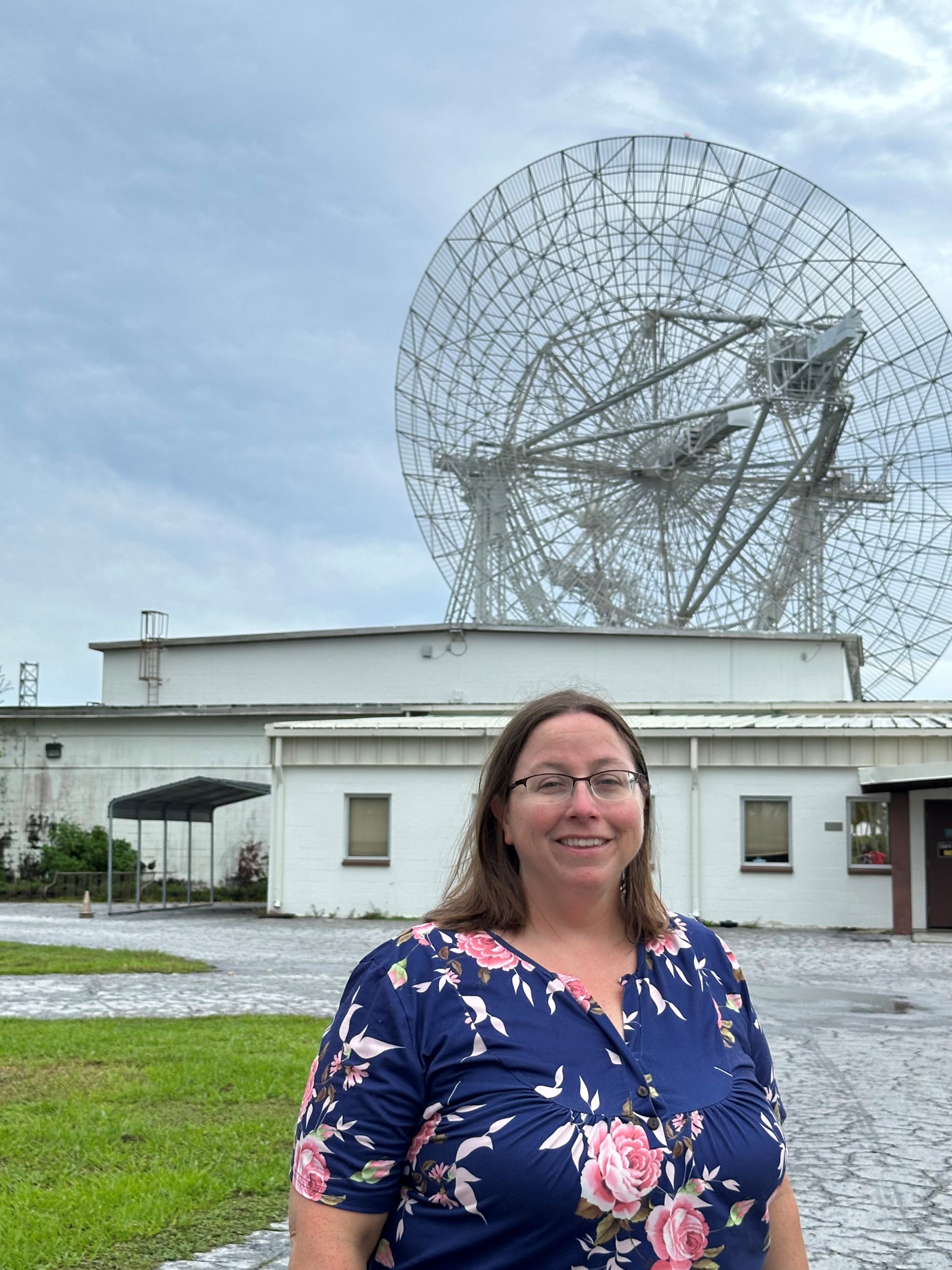

Sarah Willis reaches for the stars

Nowadays, when Sarah Willis looks up at the stars, she can see most of the Southern Sky — a view unattainable back home in Boston. This unique glimpse into sights like Alpha Centauri, the closest star to Earth other than the Sun (only four light years away), is made possible because of her proximity to the equator. For the past nearly five years, the astrophysicist-trained Willis, who joined MIT Lincoln Laboratory in 2015, has been stationed at the Laboratory's Kwajalein Field Site, which hosts radars, optics, and telemetry systems for missile testing and space surveillance. As scientific advisor to the U.S. Army's Reagan Test Site, Lincoln Laboratory supports the radar site on Kwajalein Atoll, a reef comprising approximately 100 small islands belonging to the Republic of the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean.

A passion for space emerges

Willis has been interested in space ever since she can remember. She grew up immersed in science fiction, watching "Star Wars" and "Star Trek." As soon as she learned to read, she was picking up the science news magazines at home. Her dad was a math professor, and her grandfather was an engineer who developed radars for General Electric. Little did she know that she would be following in her grandfather's professional footsteps, traveling half a world away to the Pacific to work on radars.

Willis started her undergraduate studies in astronomy and physics, but her interest in multiple areas led her to delve into math, computer science, chemistry, geology, and psychology. When she transferred from the University of Iowa to the much-smaller Loras College, she decided to stick with math as a foundation on which to diversify in graduate school. While pursuing a doctorate in astrophysics at Iowa State University, she was accepted into a predoctoral fellowship at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, where she spent the last two years of her graduate studies. Her dissertation research focused on tying together our understanding of the star-formation process in our galaxy, seen through observation of individual stars and planets forming around stars, with our understanding of the star-formation process of distant galaxies, perceived from extensive areas of brightness from infrared (IR) or ultraviolet light. Willis continued this research during a follow-on one-year postdoctoral fellowship at the same center.

During her graduate and postdoctoral work, Willis shared her passion for astronomy by joining the American Astronomical Society Astronomy Ambassadors Program, which provides early-career astronomers, from undergrads through new faculty, with training and mentoring experiences that prepare them to engage with the general public. As Willis explains, astronomy has considerable appeal because people like to speculate about big questions like, "What other life might exist in the universe?" The professional astronomy community has done considerable work to leverage that appeal as a launching point into broader STEM. She also volunteered at a local science museum and co-hosted planetarium shows and live star parties (at which telescopes are set up to view the night sky) at her graduate alma mater.

A career takes flight

When it came time to start her career, Willis was uncertain that her astrophysics background and skills would be transferrable. But the Systems and Analysis Group, part of the Tactical Systems R&D area at Lincoln Laboratory, thought otherwise when she presented her dissertation research to them. The group — which evaluates issues related to air vehicle survivability for the U.S. Air Force — saw how the same physics Willis applied to look at stars could be applied to look at aircraft.

In fall 2018, Willis attended an information session on the Kwajalein Field Site, and, nearly three months later, she was there.

"You may not know what will turn into a good opportunity, but you need to be flexible and try new things when you can," Willis says. "One of the reasons I like the Lab is that they're supportive of a broader technical exposure. I don't have to do this or that one area but can learn about many different areas."

And learn Willis did. She transitioned from her work at the Laboratory’s main campus in Lexington, Massachusetts — focusing on the science side of the common physical phenomena (albeit at very different scales) relevant to looking at stars and aircraft — to her work at Kwajalein with the site's suite of sensors. That transition required a pivot from IR systems analysis to radio-frequency hardware development.

Her first role was as sensor lead for the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) Lincoln C-band Observables Radar (ALCOR), a long-range imaging radar operating in C-band frequencies. She started leading activities to rehabilitate ALCOR — including replacing its outdated weather-protective radome — to support the next decade and beyond of mission activities. Next, Willis served as sensor lead for the high-frequency, high-resolution Millimeter-Wave Radar and the low-frequency ARPA Long-Range Tracking and Instrumentation Radar (ALTAIR), the site's biggest radar. Since November, she has been serving as deputy site leader.

"Over the past couple of years, I've been helping RTS understand where the RTS customer base [of government agencies] is going over the next 10 to 20 years and where we need to modernize and improve capabilities of instrumentation to support future test goals."

Typically, one or two days per week, Willis is on Roi Namur, the island where most of the radars are located. On these days, Willis engages with the technical contractor that operates and maintains the radars, digs into various parts of the hardware depending on specific project goals, and interfaces with sponsors.

STEM outreach extends to local community

Outside of her technical work, Willis continues to share her passion for astronomy and science with the local community. When she arrived at Kwajalein, she built an astronomy outreach program that organizes telescope-viewing events around interesting astronomical phenomena like lunar eclipses, new comet appearances, and the "great conjunction" (close approach) of Jupiter and Saturn.

Willis has also been hosting public astronomy talks, which she describes as "live-air planetarium shows." Talks have covered topics including the great conjunction and solar system, the uniqueness of Kwajalein's skies, and the connection between the search for water and the search for life in the universe. This fall, some of these live talks (and the telescope) were brought to Ebeye, Kwajalein's most populous island. The theme of the initial talk, which was translated into Marshallese, was great voyages. As Willis explains, the talk "tied together how astronomy has impacted Marshallese culture — bringing in a couple of Marshallese legends associated with stories about journeys and how those legends are captured in constellations with Marshallese oral traditions, as well as how Marshallese use stars for celestial navigation — to the concept of looking forward to the great voyages of starting to explore the solar system."

Willis' impact has extended to the local student population, which lives in a community plagued by poverty, overcrowding, limited resources for daily living, and climate change. In 2020, she helped bring to Kwajalein the highly successful Beaver Works project-based courses that she previously assisted with and led in the United States. The COVID-19 pandemic provided a ripe time to engage with high-school students who would otherwise be off island during the summer. The first year, 14 students from Kwajalein enrolled in the Beaver Works Summer Institute (BWSI), taking the Serious Games and Artificial Intelligence course. In the second year, Willis and colleagues focused on integrating students from Ebeye in the program, and a new course was offered: Mini-RACECAR (programming self-driving model cars). This same course was offered in year three, and, in year four, both Mini-RACECAR and Medlytics (intersection of data science and medicine) were offered. The ability to offer two courses in 2023 was made possible in part by recruiting a staff member from the states, Jordan Wynn, to spend four weeks on Kwajalein as an instructor. Since beginning, the program has grown to 30 students.

To Ebeye, Willis also expanded a LEGO robotics program initiated by another staff member, Karyn Lundberg, on Kwajalein. This expansion required working with local schools on Ebeye to address resource constraints and ultimately provide the fifth- and sixth-grade students with robotics kits and computers for doing the necessary coding. But the part Willis is proudest about is students paying it forward; Beaver Works alumni are now mentors and coaches for the younger students involved in LEGO robotics, working under the supervision of Mark Smith, leader of the Kwajalein Field Site. One alumnus, their first Marshallese student planning to attend college to study computer science, has already mentioned a desire to return to serve as a teaching assistant for Beaver Works.

"The Lab has been physically present on Kwajalein for the last 60 years, but, over the past decade, we've increased our focus on what we can do to improve the daily life of everyone, including our partners and host nation," Willis says. "Out here, climate change is a very real experience — we're lying on an island only six feet above sea level. An outward migration is continuing at a brisk rate, and few opportunities exist here for students to get STEM exposure like they do in the states. The Lab’s programs are equipping students with STEM skills and career awareness so that they're able to pursue a broad variety of careers, whether they remain here or move elsewhere as some of the world's first climate change refugees."

New opportunities await

For her many accomplishments, Willis was recognized with a 2023 MIT Excellence Award in the Outstanding Contributor: Working Behind the Scenes category. The award is for teams or individuals who "consistently go above and beyond without fanfare; fill in when and wherever needed and always performs at a high level; take initiative to solve problems and improve work situations without being prompted; demonstrate reliability, perseverance, and a focus on results; and help others by sharing knowledge."

During her remaining time at the Kwajalein Field Site, Willis will continue to help execute the portfolio of modernization work to prepare the range for the next decade of testing. And she will continue recruiting volunteers to carry on the legacy of outreach.

When Willis returns to the main Laboratory campus, she will again have the chance to take a leap and explore a new area.

"I think there will be a confluence of time and opportunity," says Willis. "I'm sure I’ll enjoy whatever comes next, though I can't predict what that will be!"

Inquiries: contact Ariana Tantillo.